Chromaturia, the abnormal discoloration of urine, is a clinically significant but often misunderstood phenomenon. It can signal a benign dietary influence, a predictable response to medications, or, in some cases, an underlying pathology requiring timely intervention. Understanding the contributing factors is essential for clinicians, pharmacists, and supply-chain stakeholders in the pharmaceutical sector including organizations such as a nitazoxanide wholesaler because accurate interpretation of chromaturia impacts patient counseling, pharmacovigilance, and diagnostic accuracy.

This article provides an in-depth examination of how diet and medications influence urine coloration, the biochemical mechanisms underlying these changes, and best practices for distinguishing harmless variations from those requiring diagnostic escalation.

1. Overview of Chromaturia

Chromaturia refers to any deviation from the typical pale-yellow hue of urine, which itself results primarily from the pigment urochrome. Variation arises when exogenous substances (such as pigments in food or colorants in medications) or endogenous compounds (such as hemoglobin derivatives) are present in appreciable concentrations. Clinicians rely on careful history-taking to determine whether chromaturia stems from dietary factors, pharmacological agents, or potential disease states such as hematuria, rhabdomyolysis, or porphyria.

2. Dietary Influences on Urine Color

Dietary components are one of the most common and least harmful causes of chromaturia. Although the color changes can be dramatic, they rarely indicate pathology. However, understanding these effects is important to avoid unnecessary diagnostics.

2.1 Vegetables and Natural Pigments

Certain vegetables contain naturally occurring pigments that pass into the urine after metabolism. For example:

Beets can cause red or pink urine, a phenomenon known as beeturia. This occurs when betalain pigments are not fully degraded in the digestive tract.

Rhubarb may impart a dark yellow or brownish hue.

Carrots and foods high in beta-carotene can intensify yellow urine.

These color changes depend significantly on the individual’s stomach acidity, gut microbiota, and metabolic rate.

2.2 Food Dyes and Processed Products

Artificial coloring agents found in candy, beverages, and processed foods may also produce vivid hues. Blue dyes can yield greenish urine when mixed with natural urochrome, while strong red dyes may mimic hematuria. Because these dyes are engineered for stability, they often survive digestion and filtration.

2.3 Hydration and Concentration Effects

Fluid intake cannot be overlooked. Concentrated urine appears darker due to higher pigment density, while significant water consumption produces near-clear urine. This variable often amplifies or obscures dietary pigment effects.

3. Pharmacological Causes of Chromaturia

Medications represent a more clinically complex category influencing urine color. The discoloration may result from the drug itself, its metabolites, or excipients used in formulation. In therapeutic settings, preemptively informing patients about potential chromaturia improves adherence and reduces anxiety.

3.1 Antibiotics and Antimicrobials

Several antimicrobial classes are well known for producing chromaturia:

Rifampin is perhaps the best-known example, causing orange or red urine due to the presence of rifampin metabolites.

Nitrofurantoin may produce brownish urine.

Metronidazole occasionally causes dark brown discoloration through oxidative metabolites.

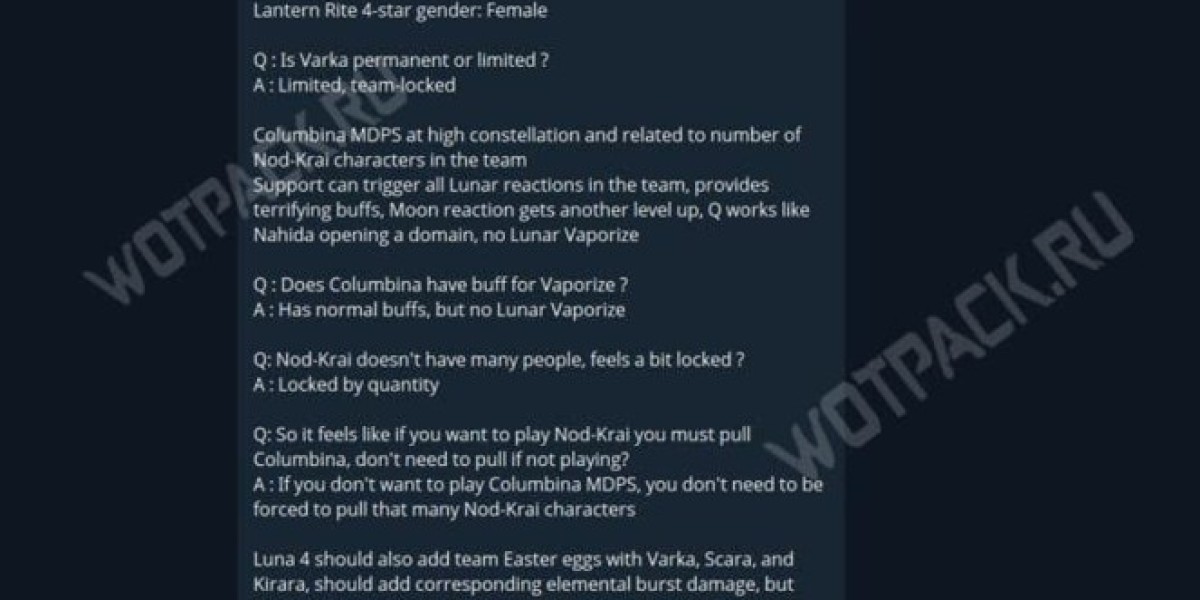

Nitazoxanide, an antiprotozoal agent, is associated with greenish or yellow-green urine in some patients because its metabolites (notably tizoxanide) can alter pigment profiles. In procurement and distribution contexts, a nitazoxanide wholesaler often includes chromatographic analysis and stability reporting for these metabolites, as they influence both product quality and patient expectations.

3.2 Vitamins and Supplements

High-dose vitamins, particularly from multivitamin supplements, also influence chromaturia:

Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) commonly results in bright yellow fluorescent urine.

Vitamin C may lighten urine or produce slight acidity-related tonal shifts.

B-complex supplements can cause variations across the yellow–orange spectrum.

Because these supplements are widely used and often self-prescribed, these benign changes account for a significant portion of non-pathological chromaturia observed in clinical practice.

3.3 Analgesics and Anti-inflammatory Agents

Some analgesics, though less commonly associated with color changes, can still contribute. Phenazopyridine, used for urinary tract discomfort, produces a bright orange to red coloration that can stain clothing and contact surfaces. It is important for pharmacies and healthcare providers to provide clear guidance regarding this predictable effect.

3.4 Chemotherapeutics and Other Specialized Agents

Certain chemotherapeutic regimens can also affect urine color. Doxorubicin may produce reddish urine for a short period post-infusion. These effects are usually transient but require explanation to avoid misinterpretation as hematuria or renal compromise.

4. Biochemical Mechanisms Underlying Chromaturia

The mechanisms behind medication-induced chromaturia generally fall into three categories:

Direct Renal Excretion of Pigmented Compounds

Many drugs are eliminated unchanged or partially metabolized, with the resulting pigments imparting color directly.Metabolite Transformation

Often, urine discoloration results from metabolites formed through hepatic oxidation, reduction, conjugation, or hydrolysis pathways. These metabolites may have chromophoric properties that differ from the parent compound.Interaction with Native Urinary Pigments

Some compounds alter urine color indirectly by modifying urochrome concentration, altering pH, or interacting chemically with endogenous substances.

Understanding these pathways assists clinicians and pharmacists in distinguishing benign chromaturia from clinically significant discoloration, particularly in patients taking polypharmacy regimens.

5. Distinguishing Benign from Pathological Chromaturia

Although diet and medication are leading causes of chromaturia, practitioners must differentiate them from pathological sources. Key indicators of concern include:

Persistent red or brown urine that tests positive for blood.

Foamy urine indicative of proteinuria.

Dark, cola-colored urine suggestive of rhabdomyolysis.

Purple urine in catheter bags (Purple Urine Bag Syndrome), associated with bacterial metabolism.

Any discoloration accompanied by flank pain, fever, or urinary obstruction symptoms.

A systematic assessment should include medication review, dietary history, urinalysis, and further diagnostics when warranted.

6. Clinical and Pharmaceutical Implications

Awareness of chromaturia is essential across clinical and supply-chain environments. Pharmaceutical distributors, including a nitazoxanide wholesaler, must maintain clear documentation on expected chromatic effects of medications to support labeling accuracy and pharmacovigilance. Likewise, prescribers benefit from incorporating chromaturia education into patient counseling protocols. This reduces unnecessary emergency visits and ensures that patients recognize when discoloration signals a benign, expected effect versus an emerging clinical problem.

7. Conclusion

Chromaturia is a multifactorial phenomenon shaped primarily by dietary intake and medication exposure. Although often benign, it requires careful interpretation to rule out underlying pathology. Clear communication between healthcare providers, pharmacists, and pharmaceutical suppliers plays a crucial role in ensuring patients understand the reasons for urine discoloration and respond appropriately.

As medication inventories continue to diversify, including specialized products sourced through channels such as a nitazoxanide wholesaler, the importance of comprehensive educational and labeling practices increases. By recognizing and explaining the mechanisms and implications of chromaturia, clinical teams can enhance patient confidence, reduce misdiagnoses, and improve overall care quality.